Eighteen years ago, Yasamma and Mariyamma Gedala were left in an orphanage in Kakinada. Yasamma, adopted by an American family, and now named Samantha Mari, has lived in the U.S. since 2000, but she still remembers her baby sister. The author pieces together the quest for reunion

On the 10th of June, 1998, in Rajahmundry, Andhra Pradesh, Nagaraju and Gowri Gedala had a baby girl, whom they named Mariyamma. They were very poor, and could not afford to feed her. On December 5 that year, they took her to Missions to the Nations orphanage in Kakinada. Ten days later, they brought their older daughter, Yasamma, born on October 17, 1996, to the orphanage too. The infant and the toddler settled into their life in the orphanage.

Then, thirteen months later, Yasamma’s life began to change again.

Over on the U.S. east coast, Patricia and Richard Tavis, then stepping into their middle years, had decided to adopt another child. They already had two sons, and each of them had a son from previous marriages. They decided to adopt a girl. And they zeroed in on India because, they were told, India did not require them to travel there in order to adopt; the orphanage would send the child to the U.S. “We have a child with autism and did not want to take the chance of something happening to us like a possible plane crash,” Ms. Tavis says in an e-mail interview.

Ms. Tavis contacted an adoption agency she found in the phone book. “Two days later they got back to me and said there was a three-year-old girl named Yasamma. I agreed to adopt her.”

While the adoption process was going on, the Tavises found out that Yasamma had a younger sister, who was also in the orphanage. They asked if they could adopt her too, but were told she had been adopted by a family in India.

A new beginning

Nine months after the first call, Yasamma arrived in the U.S., at JFK Airport in New York. “When I first came to the U.S., everything was big and scary,” she says in an e-mail. “I did not understand what was happening.” Ms. Tavis says, “When she was in the airport and we met her for the first time, we hugged and people clapped. She looked confused and bewildered after her long plane trip.”

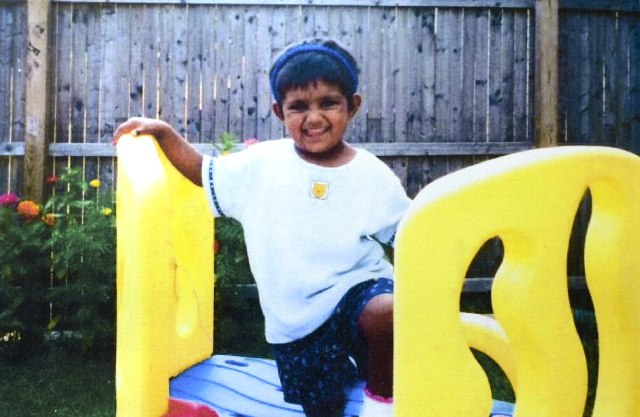

The toddler, whom her adoptive family named Samantha Mari, settled in to her very different new life, with a family that doted on her. “When she first arrived, my mother gave her a doll with blond hair and white face,” Ms. Tavis says. “She promptly coloured her face with a brown marker! Today I don’t think it bothers her that we are a different race. We are her family. As she told one of her friends, ‘They are the only family I’ve got.’”

The Tavis family has never visited India, and after Samantha was adopted, she has never returned either. Ms. Tavis has another connection, more tenuous, to India: she began studying yoga, at a local school; she graduated in 2009, and now teaches gentle, chair and special needs yoga.

Samantha is now 19, has graduated from high school, has learned to ride horses at a local riding school, and has as full a social life as any American teenager.

Shadows of the past

“My daughter still grieves the loss of her birth family,” her mother says, “and I believe this is the reason for the learning and behavioural difficulties she exhibited from the time she arrived in the U.S. It has been a difficult road; she has a learning disability, which of course, complicates matters. She learned English very quickly, though. She does not spell very well. Even though she graduated from high school, she was in special education throughout school. I hope if we find what happened to the sister, she will have some peace of mind.”

Because she was old enough to know what was happening all those years ago, Samantha remembers those days clearly. “I remember my newborn sister and sleeping in a railway car with my parents and her,” she writes. “I remember the railway car. I remember a boy at the orphanage who would bring me toys. He made me feel like a queen! I think he was my first boyfriend! I remember not having shoes and sleeping on mats. We ate rice. I remember Paparao [Papa Rao Yeluchuri, current director of the Mission to the Nations].” Ms. Tavis adds that she has at times also said that she remembers that she cried a lot, that she remembers being in the street, picking up papers, that she remembers being left at the orphanage.

“As soon as she could speak English,” her mother says, “she told me she was ‘very mad at mommy and daddy in India’ because they left her by herself. Truly this experience scarred her deeply even though her parents put her up for adoption to give her a good life. She has asked about the sister from the time she arrived, always wondering what happened to her baby sister. Even though she was young, I believe these memories are so vivid because they were so traumatic. She would like to know what happened to her, be able to talk and write to her and maybe one day meet her.”

This is something Ms. Tavis vowed to herself that she would do something about. But she had no idea how to even begin looking for Mariyamma; also, what if the younger sister’s adoptive parents did not want her to know she was adopted? She decided that she would wait until Mariyamma was a legal adult.

A quest begins

In June, Mariyamma would have turned 18. And Ms. Tavis made a Facebook post. Along with what little she knew of the Gedala family, she wrote, “I am asking my friends and family to share this far and wide so my daughter might know the baby sister she still remembers and longs to see again.”

That post, and another she made on a page she runs for her yoga practice, quickly went viral. In a couple of days, they were shared over 2,000 times, including in India.

In an update thanking people for sharing her message, she also addressed the concern about the wishes of Mariyamma’s adoptive parents. “I agree that this is a concern. This is why I waited until her sister was 18. I believe it is a basic human right to know where you come from and who your family is. Because my daughter was old enough to remember her family when she was brought to the orphanage, she has suffered a great deal of heartbreak. I am trying to give her back a little of what she lost.”

Dead-ends

In the days since, her post has been shared 5,327 times on Facebook, aside from numerous shares that did not reflect there because they were made on other social networks. While many reached out to help, the family has not got any leads so far.

The Hindu’s reporters reached out to both Mission to the Nations and the State’s Women and Child Welfare (WCW) department.

Mission to the Nations, an NGO in Kannaiahkapu Nagar, Kakinada, no longer runs an orphanage; they closed theirs some years ago, after an adoption racket surfaced in Andhra Pradesh. The government took over all its records and the organisation now only runs a church and a school. “The adoption was done through the court of law and the communications were made between the embassies of India and the U.S.,” said Papa Rao Yeluchuri, its current director. “Following the adoption, the girl’s parents never visited us in person and we do not have any detail about their whereabouts.” He added that the Supreme Court’s guidelines prohibit the disclosure of the details of biological parents to the adopted child.

In this Yeluchuri seems to be behind the times: there is, in fact, no Supreme Court guideline prohibiting an adoptive child from knowing her biological origins; such knowledge is part of a person’s essential right to know and right to privacy. It is left to the adoptive parents’ discretion to inform their minor child about her origins. There is also no restriction whatsoever on an adult about going in search of her biological parents. The lacuna in law on this aspect was cleared by the Supreme Court in its Laxmikant Pandey versus Union of India AIR 1984 SC 469 judgment. The new Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act of 2015 provides for revamped intra-country and inter-country adoption guidelines. On the rights of siblings, the interest and welfare of the child is considered paramount. There are many laws on guardianship and parental custody, and disputes are decided on a case-to-case basis. The courts are careful to not let the rights of a sibling and the custodial rights of parents cancel each other instead of complementing one other.

Sivanath Yandamoori, chairman of the Child Welfare Committee (CWC), East Godavari district, toldThe Hindu that Yasamma has every right to know about Mariyamma, as the court is clear about retaining the bond between siblings. “This is a rare case,” Yandamoori said, “The CWC can help Yasamma meet her elder sister, provided she comes to India.”

While the Tavises were delighted to hear this, the news brought back an old dilemma.

The family lives a reasonably comfortable life in Howell, New Jersey — “near the famous Jersey Shore,” Ms. Tavis says — but they’re not wealthy. Richard is 62, and recently retired from Pepperidge Farm, where he was a manager. Patricia is 59, and has been running a yoga practice since 2009. An indefinite trip to India without solid leads to follow up on is a prospect that is too expensive for them at their time in life. While their older sons are married and have children, the two younger ones live with them. The younger lad, Christian, 20, balances college and a job at a supermarket. But James, 24, has an autism spectrum disorder. They worry about his future, about who will take care of him when they are gone; he’s also one reason why they don’t like to take air trips. But if they do find Mariyamma, Ms. Tavis says, they will try and help the girls meet. But that prospect is still dim.

Ms. Tavis has also stepped back from her Facebook campaign; the volume of people asking how they could help the family was staggering and touching, but it also brought out the darker side of such Internet interaction: “unwanted attention from men”, as she delicately phrased it, both for herself and Samantha.

The possibility has also come up, as a source (whose name Ms. Tavis does not want to reveal at this time) told her that Mariyamma may have been returned to an orphanage elsewhere and been adopted again. The paper trail is, in all probability, dead. So a documented relationship might be impossible to establish.

Hope lives

But science may be able to help. The least complicated would be a blood test, through which some degree of relatedness could be established. Any decent hospital, and a number of private organisations, would offer more sophisticated methods like genetic testing. A boy, for instance, would inherit his father’s Y chromosome, which is why that method is used to determine paternity.

Then there’s mitochondrial DNA (mDNA), which all humans inherit from their mothers: mDNA undergoes very little mutation over generations, so is considered a very accurate way to determine genealogies. Siblings like Samantha and Mariyamma will share the same mDNA. The tests are simple, but since India’s laws prohibit DNA being exported, Samantha and Mariyamma would need to be tested in labs on different continents.

This is only valuable if — and it’s a very big if — the search does bring forth a young woman who is a likely match. Mariyamma must be found. Which is where you, dear reader, can help. If you have any information for the Tavises, e-mail FindingMariya1@gmail.com or this writer (peter.griffin@thehindu.co.in). Because a story like this really, really needs a happy ending.

With additional reporting from K.N. Murali Shankar and B.V.S. Bhaskar, and inputs from Jacob Koshy and Krishnadas Rajagopal.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Opinion> Comment / Peter Griffin / August 20th, 2016