On this typically steamy day in Kakinada, doctors have been performing cataract surgeries all morning. There are still dozens of surgeries to go when the power goes out. I flinch and start to panic. The doctors, however, carry on like nothing happened. It feels like forever, but is actually less than 20 seconds before the hospital’s backup generator kicks in.

LAURA STRICKER The Sudbury Star Cataract surgery patients board the bus which will take them back to the village of Rowthulapudi, 50 kilometres from Kakinada.

I’ve been in India for more than a week and am used to the sporadic power outages. But tucked away in the corner of the operating room at the Srikiran Institute of Ophthalmology, trying to stay out of the way and make myself as small as possible, the lack of electricity makes me nervous.

For the staff, it’s just another part of working in a country where providing reliable electricity for more than one billion people has long been a challenge. One of the biggest expenses the institute has is to keep its generator running. But all that is worth it, I’m told, because they’re helping people who would otherwise spend their remaining years languishing in their homes, unable to take care of themselves.

Nalam Amalu is one of those people. When she had her first cataract surgery in 2009, it was after she’d been blind in her right eye for two years.

So, when the vision in her left eye started to go a few months ago, Amalu, 65, knew she had to go back to Srikiran. The institute was established in 1993 to help people such as herself, who have eye problems but don’t have the money to get care, or access to a hospital.

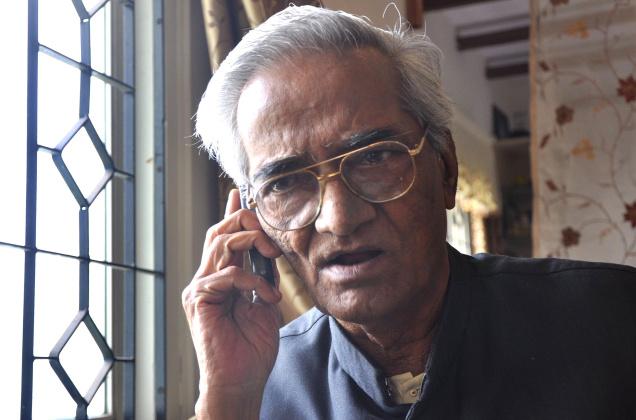

The Manjari Sankurathri Memorial Foundation, set up in 1989, runs and funds the hospital. Chandrasekhar Sankurathri (Dr. Chandra) moved from Ottawa to Kakinada and founded the organization in his family’s memory. Manjari, his wife, Srikiran, his son, and Sarada, his daughter, were killed in the June 23, 1985 Air India bombing.

“When I got my right eye operated on, I was thankful to God for sending a person like Dr. Chandra, who is able to conduct these (eye testing) camps and give sight to so many people who are neglected,” Amalu says. A short, skinny woman, the bangles on her wrists clank as she uses her torn shawl to wipe her nose and eyes.

She lives in S. Pydipala village, she explains, speaking in the local language Telugu. The village is six kilometres away from Rowthulapudi, the site of the testing camp. To get to the camp she paid 10 rupees ($0.18 Canadian) for a car ride.

“I don’t have anybody to take care of me,” she continues. “I’m so grateful to Dr. Chandra and the hospital for giving me sight again.”

Men in India are more at risk to get cataracts from working in the fields without eye protection, staff members at the hospital say. But at Srikiran, more women — who often get left behind — are the ones getting the surgery.

On average, after getting the surgery, patients see their vision improve by 90%. Infection is a common problem, though, as they don’t follow post-operative care instructions and lack the clean water necessary to wash out the eye. Even after the surgery, most people need eyeglasses. For those who can’t afford to pay, the glasses are given to them for free.

On the day of the surgery, 100 people wait patiently for their turn, sitting on thin mats scattered throughout a long room. Nurses walk from person to person to confirm identities by asking their name, which eye is getting operated on and the name of their husband or father — a step that gets repeated at every stage before the surgery. Each patient has a white sticker put over the eye getting operated on.

These surgeries, hundreds of which are performed every week, have an impact that goes beyond just improving vision.

“When people become blind, they cannot be productive citizens in the community, and somebody has to look after them,” says Dr. Chandra. “When they’re already poor and they cannot make a living because they are blind, and then another person has to look after them, this puts even more economic strain on the family.

“So, for such people, we are providing free eye care and also restoring their eyesight, completely free of cost to them. By doing so, we are making them a productive part of the family and the community again; thereby the economic burden is eased. They also get their self-respect and confidence restored.”

Another patient, who gives her name as K. Mallamma, says her restored vision means she can help her son, who lives with her, with his business.

Since January, she’d been losing vision in her left eye, she tells me through a translator. It got so bad she couldn’t see to walk the short distance from her house to get fresh water.

“Now I can move around, now I can do a little bit of housework, like sweeping. Before I was not doing these things. My son was doing those things. But now I will be able to do all that.

“At least now I’ll be able to help my son (who does laundry for people in their village) a little bit. Like when he irons the clothes, I’ll be able to fold them.”

With one cataract surgery costing $50, and 90% of the surgeries done for free, Srikiran survives largely on donations, says Dr. Chandra.

“In this aspect, I think we are very unique in India, because nobody else does that many free surgeries. And it is possible for us because several people in Canada are supporting us, from the east coast to the west coast.”

These donations also go to cover the cost of operating four vision centres outside Kakinada. If patients have problems after the operation, or have a post-operative checkup, they can go instead to one of these centres if they’re closer than Srikiran. A computer at the main branch of the institute connects via webcam to the centres.

For those who need the surgery, getting them to the post-operative stage isn’t always easy.

“Sometimes they don’t even want to come because they’re so disappointed in life, some of them are very grouchy and sad. But we tell them look, you come with us and we’ll try to help you as much as we can,” Dr. Chandra says. “So when they come, the next day when you take off the bandages, you should see the feeling in their face. It’s really hard to describe it.

“When you see those happy faces, that gives us maximum satisfaction — to see the value of what we are doing.”

Kotipalli Iswaiamma, 75, was initially scared to get the operation and unco-operative at the field camp. After the surgery, she was so overcome with emotion, she had trouble speaking.

Ten years ago, she hit a wall and lost all sight in her right eye. Six months ago, the vision in her left eye started getting worse.

This was a big problem because she looks after her husband, who is completely blind.

“I have to take care of all his needs,” she says, including taking him to the toilet and bathing him. “He stopped eating food. Instead of having three meals, he only has one so that he won’t go to the toilet as much.

“Now at least vision in my one eye is good, so I can take care of my husband,” she adds, her voice wavering.

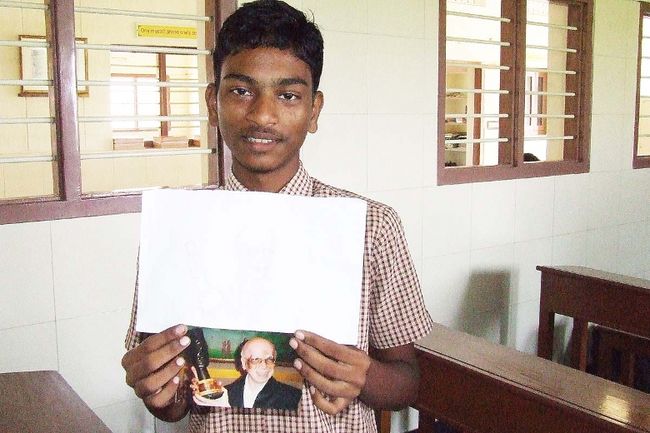

Laura Stricker photo. Guttula Manikanta, a grade 10 student at Sarada Vidyalayam school, shows a picture he drew of Chandrasekhar Sankurathri, founder of the Manjari Sankurathri Memorial Foundation.

Reflecting on the nearly 180,000 eye surgeries performed and the students that have a brighter future, Dr. Chandra says his family would approve of what he’s doing.

“I think they would be very happy, and that gives me a lot of satisfaction,” he says softly. “It’s what I do with my life now. I have no regrets about it. I’m very happy with what I do. I always wish I could do more.

“Something always at the back of my mind is to look after women and child health, because there’s a lot of problems with child-bearing women,” he continues. “Their health is not very good. Infant mortality is the one thing we want to address sometime in the near future.

“I just want to thank all the supporters across the country, and especially in Sudbury. We really appreciate their support and are looking forward to having the same support in the future, to ease some of the suffering of the poor. I really thank from the bottom of my heart.”

— Star reporter Laura Stricker’s trip to India was funded by the Ontario International Development Agency, a longtime supporter of the Manjari Sankurathri Memorial Foundation. For more information on the organizations, visit www.msmf.ca and www.ontariointernational.org. Read Accent every Saturday.

laura.stricker@sunmedia.ca Twitter: @LauraStricker

source: http://www.thesudburystar.com / The Sudbury Star, Canada / Home> NewsLocal / by Laura Stricker, Sudbury News / Saturday, December 29th, 2012